In the Paint

Artist Aaron Hazel ’07 explores the human experience through his work.

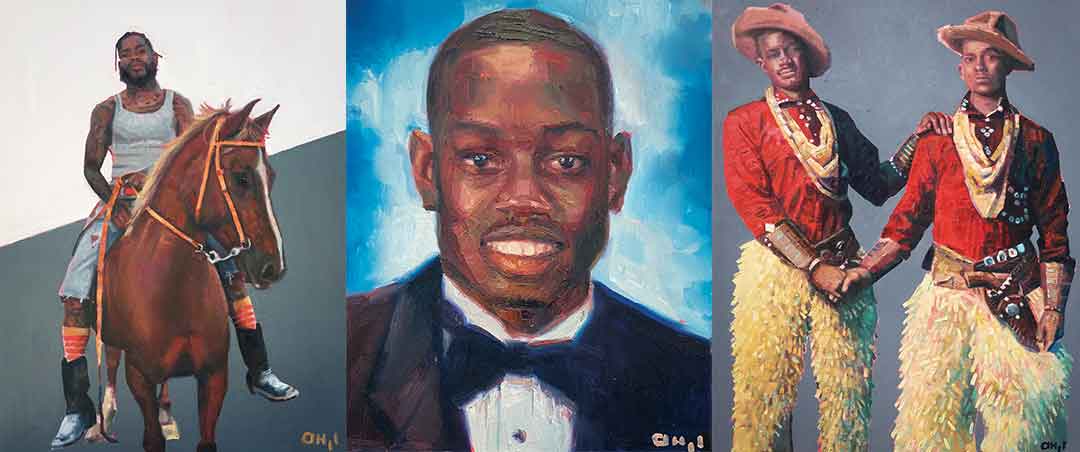

When a video of jogger Ahmaud Arbery being shot and killed hit the news in May 2020, Aaron Hazel ’07 painted two portraits.

The first was from a photo of Arbery grinning in a tuxedo.

The second was of Travis and Gregory McMichael, two of the men later charged with murdering Arbery.

Hazel tearfully painted Arbery, a person of color like him. In the past, he’d tried to emotionally distance himself from similar stories, but Arbery’s death compelled him to take action.

He felt sick as he painted the McMichaels.When the piece was done, he filmed himself punching through the canvas, then taped the shredded remains to the wall of his studio in a cathartic act of performance art.

From then on, Hazel committed himself to commemorating unjust deaths in paintings he does not intend to sell. He painted George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain. He painted Sean Monterrosa, shot by police who mistook a hammer for a gun, and Walter Wallace Jr., a man with bipolar disorder killed by Philadelphia police.

Many people criticized this choice, Hazel says. He initially broke into the art world with lighter subjects—especially paintings of athletes and Western scenes—and the new work was outside his norm.

“But when things like this happen, it affects me, as it should all of us,” Hazel

says. “As an artist I have the ability to absorb, examine and communicate these moments.”

What it is to Be Human

Hazel is a prolific painter, showcasing dozens of works across galleries in the West and even more online. He tends to paint with energetic looseness while maintaining high levels of realism.

“Whenever I’m starting a painting, I can’t wait to start the next,” he says. “I love the process of painting, but there are so many things I want to paint.”

{{1-right}}

Peruse Hazel’s Instagram feed (@ahaze2) and you’ll see a range of subjects that fascinate him. Alongside the memorial portraits are Wonder Woman and the Wolf Man, bison and moose, 19th-century Native leaders and Civil Rights heroes, Jimi Hendrix and Nipsey Hussle. A child perches on a pair of skis, a Compton Cowboy rides a rearing horse, an early-1800s Irish laborer hefts a basket on her hip. Not every piece is a portrait, but most focus on faces.

“I feel like when I paint a face, I’m deeply engaging myself into every facet of that person’s being. At that moment, all I can think of is them,” Hazel says. “I’m creating this super intimate experience with them.”

Hazel never dreamed of being a full-time artist when he was growing up in Boise. He majored in art while playing basketball at Whitman, thinking he’d go into advertising or marketing, or even continue his hoops career.

While he laments not spending quite as much time in the studio as he did in the Beta Theta Pi house or on the court, he loved learning from incredible artists on the Whitman faculty, especially retired professor Keiko Hara. His professors introduced him to oil painting and pushed him to rethink his concept of fine art.

He found support in other areas, too. The late Whitman sports information director Dave Holden encouraged Hazel to show his art for the first time, in a pre-game exhibition. Hazel was nervous, but he sold two paintings—one to a professor, one to his grandmother.

“It put a seed in my brain, thinking, ‘Wait, maybe I could sell a few paintings on the side someday while working my corporate job,’” he says.

After college, he studied with Declo, Idaho, painter Robert Moore, who helped him refine his style. Moore says Hazel’s hunger for art reminded him of his own passion as a young man. Over the years, he’s watched Hazel develop his ability to create a piece that works on multiple levels, beyond recreating a likeness.

“There’s a design within the design, and that’s where I’ve seen him just blossom and be able to evoke emotions from his images and his paintings,” Moore says.

So Many Stories to Tell

Hazel was bartending in Bellevue, Washington, in the early 2010s when Seattle Seahawks players started commissioning his work. After the Seahawks won the Super Bowl in February 2014, Hazel was flooded with requests. That May, he quit bartending. He’s since returned to Boise, supplying galleries, fulfilling commissions and painting whatever strikes him.

Recently, he’s focused on underrepresented figures, especially indigenous people and Black cowboys. He works off historical photographs, reading about people as he captures them on canvas.

“This is a great chance for me to unearth the lesser-known stories of the Old West,”

he says.

He has an eye on the “New West,” too. He’s planning a photo shoot and art show with the Compton Cowboys, a group that rescues and raises horses to highlight the legacy of Black equestrians and serve their often-stereotyped city.

Hazel loves learning about his subjects and sharing their lives through his paintings. He’s got a stack of canvases waiting for the next story to tell.

“There are so many avenues of information that I’ve yet to learn,” he says. “I want to understand different perspectives and different lifestyles. I’m a sponge at this point.”